Sunset up Mount Eden, trying to outrun that pre-nights anxiety. March 2018.

It’s becoming Autumn. Days are shorter, mornings noticeably darker and cooler, leaves starting to blush, curl and fall. We’re on the cusp of change right now. On Saturday morning I got home from a night shift and my room was so stiflingly hot that I took my bedding outside onto my balcony and passed out there, woken a few hours later by intense thirst and the midday sun beating down strongly upon me. But today is Monday and the tail end of a cyclone has been lashing us with rain ever since I woke up. For the past few months I would walk to work in only shorts and T-shirt. When it rained, it was that hot and humid kind that makes tarmac steam. Today when I changed out of scrubs and left the hospital in running tights and a light jumper, I shivered in the fresh air.

I didn’t manage to put a post together in February. It was a short month anyway, but it felt as though I blinked and it was gone. I finished up my rotation at Auckland City Hospital, and took the second half of the month as annual leave. I had a bunch of lieu days to use up, so I hired a car and went on a lil solo mini-road trip. Then Sarah arrived and we spent a whole two weeks adventuring. More about that another time. I’ve started a new job (again!) now – Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Women’s Health, often abbreviated to “Obs and Gynae”, or O&G), and the night before my first day I was an adrenaline wired anxious mess. It took a few days for the nerves to fully die down. (Does changeover ever get easier??) But I’m back in Middlemore Hospital, and it felt like coming home.

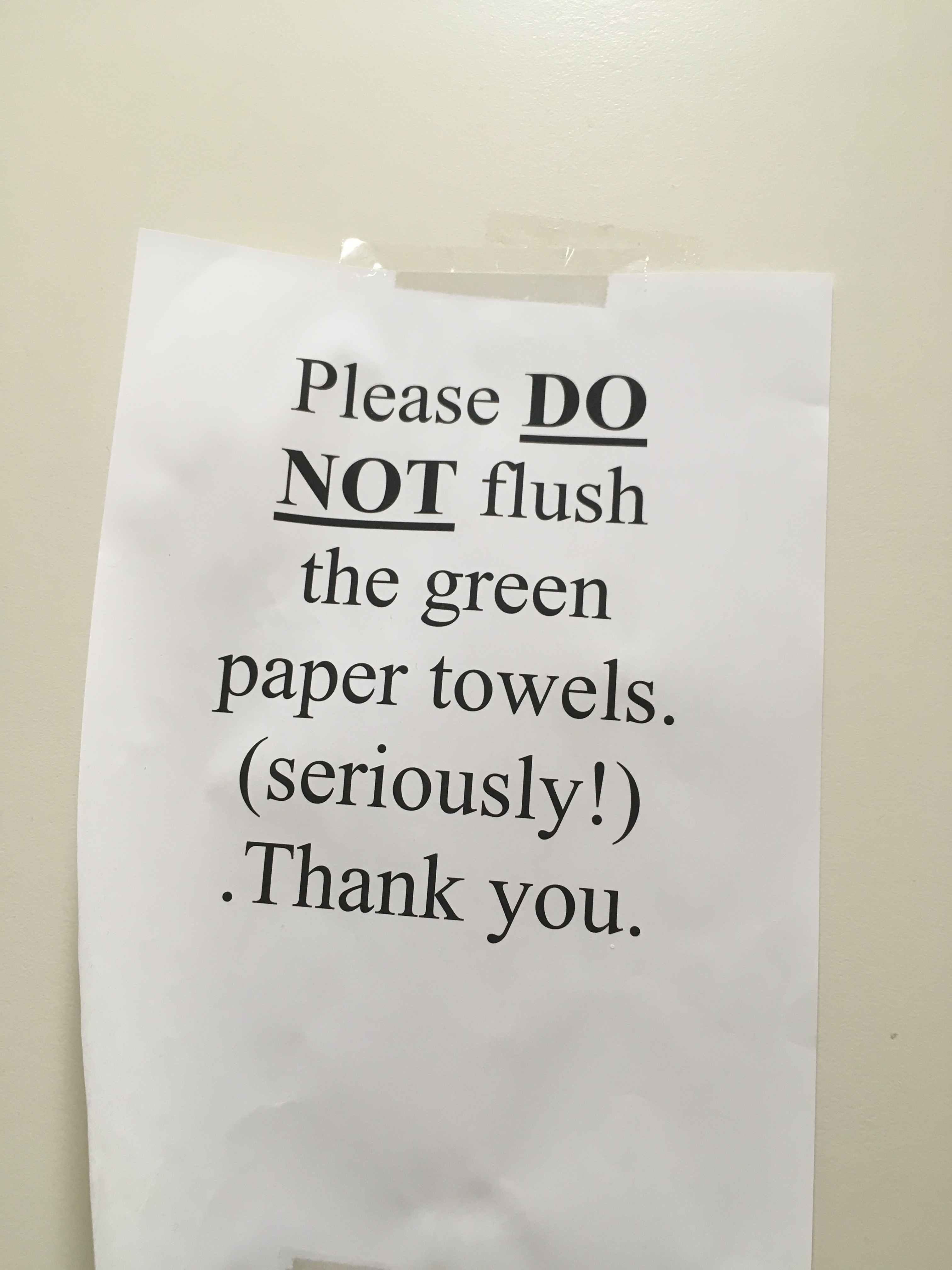

(Still loving these wonderful makeshift Middlemore posters with their unruly punctuation and SUDDEN CAPITAL LETTERS… So stoked that I get another three months of them. Also loving that friends have begun to associate me with them, and take photos of them on their phones and send them to me with a “this made me think of you!”, just like with license plates after I mentioned those in my last post. I love it, please never stop. What a legacy.)

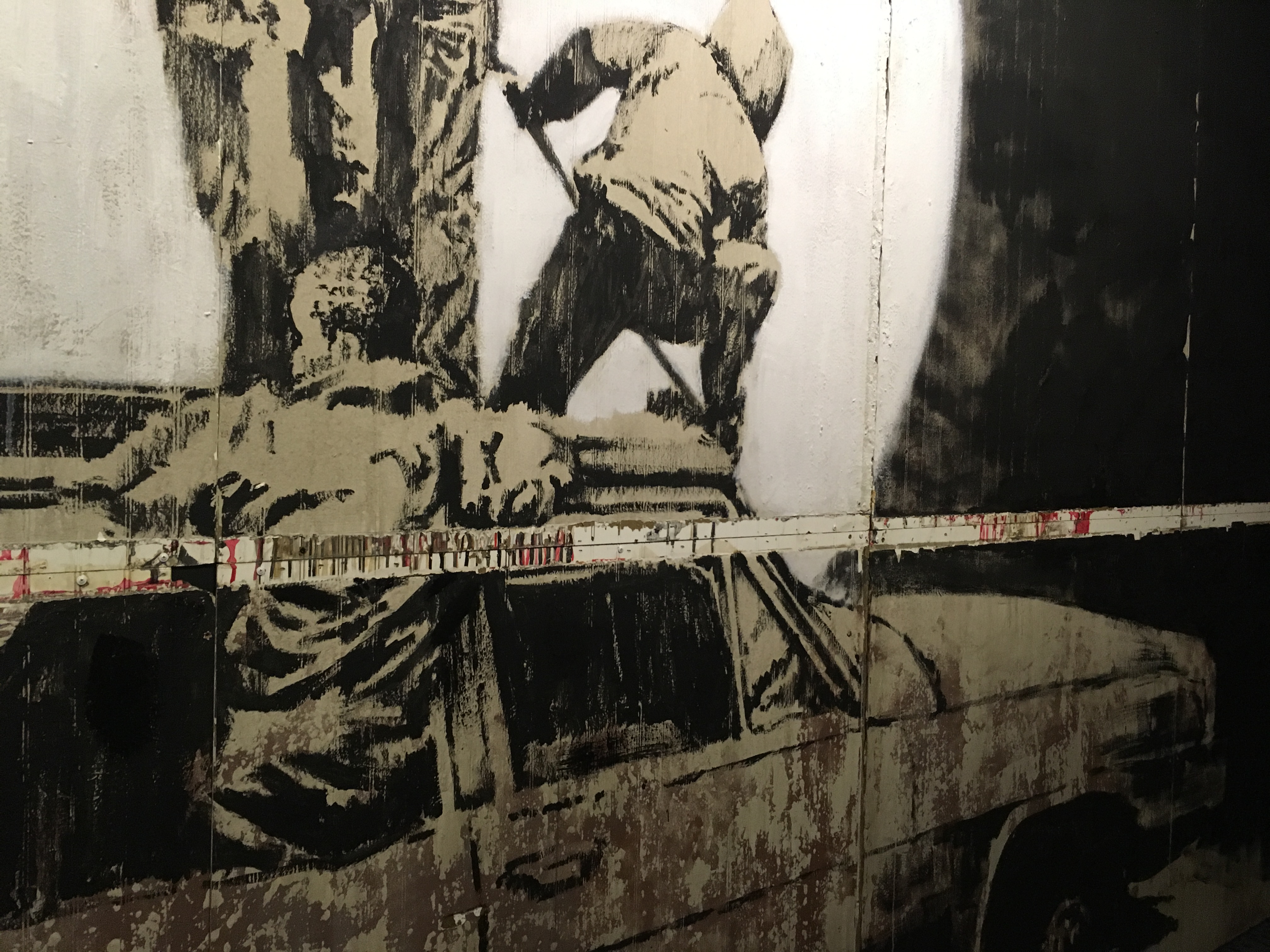

War Memorial, Auckland Grammar.

I didn’t write in February because I was away for most of the month. But even if I’d been home I’m not sure I would have known how to articulate what it was I wanted to write about, or where to start. I wrote at length about my renal rotation, and even after just one week of O&G I can tell I will have similar feelings to share, but my experience in Auckland City was different. It is only with a bit of distance that it has become more clear to me what I have taken away, what I would like to convey.

Walk to ACH through The Domain. Feb 2018.

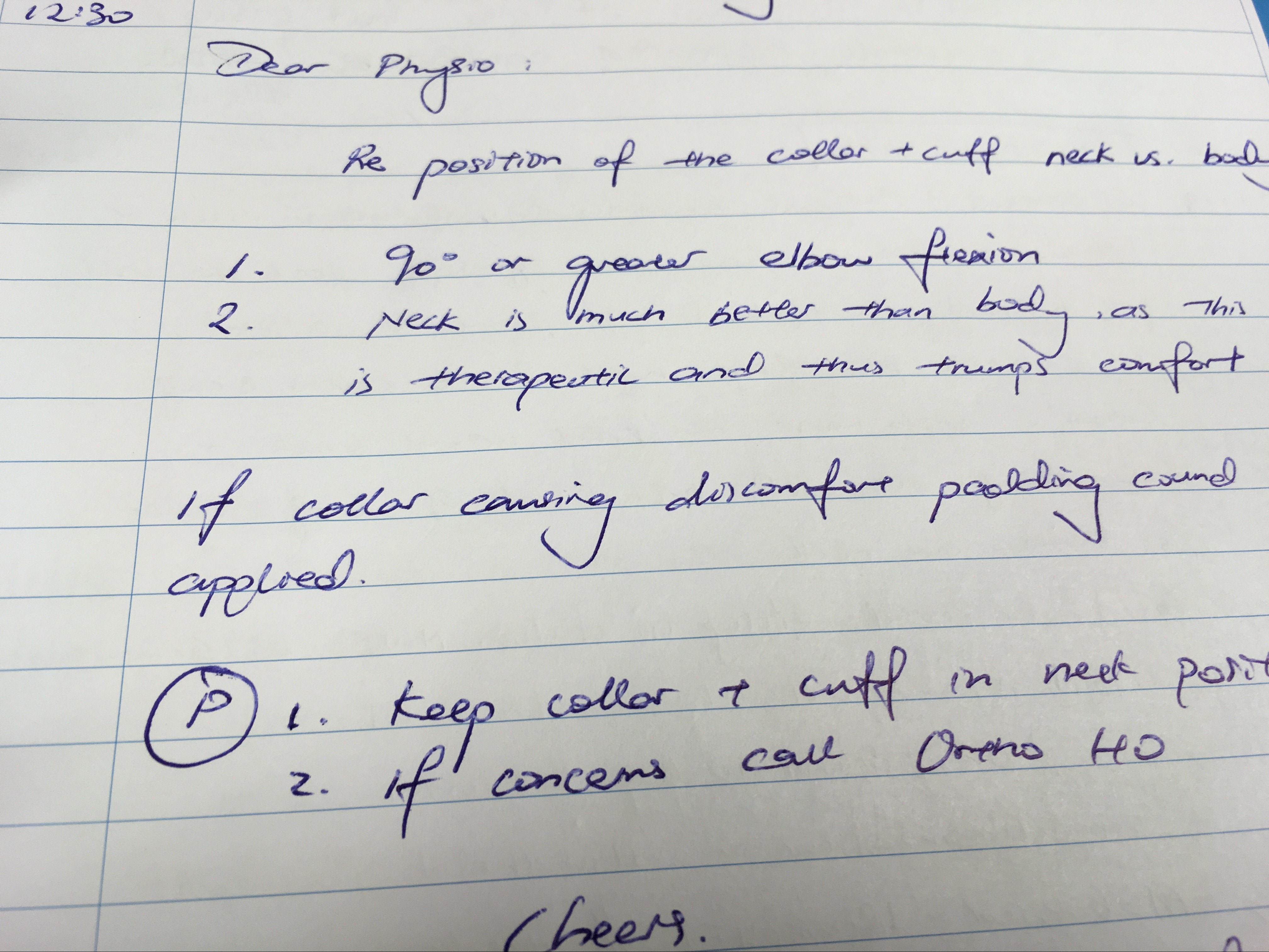

I spent my second job working in a rotator role, which is a position that (as far as I’m aware) does not really exist in the NHS. I was assigned to two specialties, Orthopaedics (which is surgery to do with bones and joints) and Urology (which is surgery to do with the male anatomy), and essentially I rotated around different teams covering the usual house officers when they were working night shifts or when they had scheduled days off after working a weekend. I didn’t cover short notice sick leave or annual leave – that role is filled by another person sorely lacking in the NHS: a “reliever”.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I began. Outwardly I’m sure I seemed just fine, inwardly I was a mess of stress and fears. After having enjoyed working so much in a team during my renal job, I worried that the lack of continuity would be lonely and difficult. In this position you only get given your rota for the immediate two weeks ahead, one week in advance, and I wasn’t sure how I would find that either (- it’s difficult to make many plans for weekends away or to book tickets to anything when you don’t have much notice about the shifts you’ll be working). Finally, but perhaps most importantly, I didn’t know how I would find Ortho or Urology. I’d had some experience of the latter in my first year; I felt pretty equivocal about it. Ortho, in the hospitals where I previously worked, had a rep for being a pretty rough job for juniors. I’d spent enough night shifts as a first year doctor covering all of the surgical wards, desperately trying to rescue incredibly sick people. The Ortho patients were always the sickest.

As it happened, I only ended up covering four days of Urology in the entire three months. That was basically the luck of the draw, but it suited me just fine. I needn’t have worried about not feeling part of a team – although there were five separate Ortho teams (all named after the day of the week that their consultants were “on take”) there was a really good group of other house officers, a well structured relationship with the physios/occupational therapist and pharmacist (who were all lovely), and really supportive experienced nurses, so it just felt like being part of one big community. Being officially unattached to a team also had the bonus of meaning I could dip in and out of anyone’s operating theatre without offending any of the bosses (usually you would be expected to go into theatre with your own team – which limits the range operations you might see if your bosses are all spine surgeons, for example). And at the end of the day I did actually spend most of my time with the Thursday and Friday teams, which allowed for a little bit of continuity. As for the planning your life side of things – there were a couple of occasions on which it was a little frustrating, but by and large it really didn’t bother me all that much, which probably won’t come as a surprise to anyone who really knows me haha – not quite sure if you would cope, Joel ;)

As for the work, I loved it. Morning starts would be around six thirty, but we’d usually be able to get breakfast by nine, and it was always pretty cruisy. Even on the busiest team, if you kept up a good pace and didn’t get thrown any curveballs, you could count on being done with jobs and able to leave on time unless it was the day that you were “on take” (ie, admitting all of the new patients who came into the emergency department). We were lucky in that the job fell over the Christmas- New Year period, where a lot of the surgeons take a couple of weeks off work to go on holiday, so for a while there were no clinics or elective operating lists (“elective” meaning one of the standard operations that are scheduled throughout the year and aren’t emergencies, such as routine knee replacements, as opposed to say a smashed up leg from a car crash). And in perhaps the most surprising twist of all, I found myself really enjoying Orthopaedics! Really, really enjoying it. Back in the UK I only did one surgical job and barely spent any time in operating theatres – the wards were too busy, the surgeons too unpredictable. This time round I spent as much time as I could scrubbed in, making the most of an opportunity I likely won’t have again.

Looking back over sunrise in The Domain as I arrive at work. ACH. Feb 2018.

(Just as an aside for my non-medical readers: “Scrubbing in” doesn’t mean wearing those pajama-like scrubs that you see on TV (we’re all in scrubs anyway), but is instead used to describe the action of getting involved in a surgical operation. If you take it literally, it means scrubbing your hands and forearms raw with anti-septic detergent, and then wearing special protective gowns, gloves, masks and caps to absolutely minimise any potential risk of infection. When you cut into people’s bodies, especially in Orthopaedic Surgery, where you’re going right down to the bone, you run the risk of introducing a potentially fatal infection, of causing more arm than you do good, so everything is geared to minimise the chance of that happening. If you haven’t “scrubbed”, then you essentially just have to stand in a corner and watch, there’s no way you can get anywhere near the patient, let alone touch them, as you would contaminate the sterile field. And just watching can get pretty boring after a while – you don’t get a great view, you’re too far away to ask questions, you don’t really understand the intricacies of what’s going on, why particular decisions are made, etc. But if the surgeon in charge lets you “scrub in” then you know that you’re gonna be able to get up close and see what’s actually going on, and hopefully get involved – which, depending on the operation and the boss, could mean anything from holding a limb in the air for a few hours, to getting to drill a few screws in or close a wound. (Obviously the more experienced/senior doctors get to do a whole lot more, usually their own operations under supervision)).

I don’t have a lot to say about the patients I treated in Auckland City. This is what I was struggling with initially when wondering what I wanted to share from the past few months. Even now it feels like a strange thing for me to write, as though I’m betraying some core part of myself. I’ve always billed myself as someone who is deeply invested in delivering good patient-centred care, in treating each person with kindness and respect, trying to understand their own particular experiences of illness, their reasons behind missed appointments, anxieties, non-concordance. And I still am, I am. I treated those patients I cared for at ACH no differently. But in a way the patient-doctor relationship is more straightforward in a surgical specialty.

Treating a medical condition usually involves trying to understand the bigger picture before zoning in on the details, taking into account the patient’s general health and home circumstances. In an ideal world, you not only address their current problem, you also optimise any other medical conditions they might have, making small adjustments to their usual medications, trying to come up with a treatment plan that will realistically fit around their lifestyle. Often they will come back with the same issue a few months later and the process starts over again. There are usually a lot of lessons (medical, personal and professional) to be learnt from what worked and what perhaps didn’t go so well.

In surgery the patient presents for a specific operation, that operation is performed to the surgeon’s best ability, and the interaction pretty much ends there. The patient is then discharged home, or entrusted to the care of an appropriate rehab team. The layers of subtlety (and lessons to be learnt) lie instead in other areas – team leadership, teaching, prioritisation. All of these skills are required in medicine too, but they take on an arguably greater importance in the surgical world, where days are structured around ensuring that theatres run to schedule, and there is often a need to act rapidly and decisively. These are the things I want to write a little about today.

When I think back over the past three months, memories of laughter and sunshine outweigh everything else. Clearly that is not an accurate objective representation, I could quite easily list specific days or events that caused me anxiety or distress, or days when rainclouds blew in from the sea and hung like a curtain outside the big glass windows of the Ortho wards, obscuring everything from view. It is nevertheless the sentiment that pervades, and I think that is telling.

The Orthopaedic department in Auckland is very much a man’s world. There is, as far as I’m aware, only one female consultant. The ratio of male to female registrars and house officers varies, but during my run there was only one female reg, only three other female house officers. While wholly polite and professional on the outside, the spirit that predominates behind the scenes is almost schoolboy-like in nature: crude, buoyant, buzzing with adrenaline and a slightly inflated sense of self-importance. The beginning of my run in December coincided with the beginning of the New Zealand medical year: almost all of the house officers were starting their first ever job as a doctor, many of the junior regs had just stepped up to their first ever reg job. Everyone was fresh and keen, eager to make a good impression.

It is amazing how rapidly you forget your first few months as a doctor, or perhaps more accurately, how readily you dismiss how far you’ve come, until you encounter real first year year doctors again. I haven’t forgotten how utterly exhausting those first shifts were, nor how thankful I was for those unknown senior doctors who stepped in assuredly and unprompted when I was at a loss. “Remember to look at magnesium if you’re replacing potassium”, “Check the bloods early on, you might need to act on something”, “Don’t worry about that, that’s a registrar’s job”, “Here, you’re doing great, come and have a cup of tea. Have you eaten? Go and eat, you can’t do anything if you haven’t eaten”. I remember the names of every one of those doctors, but I don’t think I ever managed to convey even a fraction of the gratitude I felt towards them.

Now the roles are reversed, and it was so nice for me to be that person looking out for others, and be able to pay some of those good deeds forward. The new first year doctors were a great bunch, enthusiastic and cheerful and more than capable across the board. They didn’t need much help or advice, but I enjoyed being able to be a sounding board for their plans when they handed patients over, discussing some of their more complex medical patients, reviewing medical x-rays or blood results with them, lending a hand with some of the more tricky cannulas or bloods. It was great to see their confidence (and sass) grow over the course of the rotation. It made me realise that I am ready to step up and assume more of a leadership role.

Sunlight arriving after the end of a long night. Middlemore. March 2018.

Meanwhile, I watched with interest and a great deal of respect as the junior regs settled into their new jobs. Most of them were at the same level as me (three years out of med school), and I was impressed every day by their attitude. They were expected to work much longer hours than they were rostered to, coming in earlier every morning and informally checking in on their patients every weekend, but I never heard any of them complain about this. Every morning they would attend a meeting in which the consultant surgeon on-call for the day would review the list of patients awaiting operations. The role of the juniors would be to put forward the case for any patients under the care of their team, while the reg who had been on-call overnight would present any one he had admitted. It was a rough job for the night reg, who would do seven nights in a row, and be expected to stay on for a few hours in the morning to post-take all of the patients that had come in overnight. The consultants viewed the occasion as one to quiz and educate; the teaching was good, but ruthless – the air could turn blue within seconds. “Think you could handle that operation on your own?” one of the regs was asked (rhetorically) in one of the first meetings I attended. “Your hands were shaking like a paedo in a playground!” – this to a sardonic outburst of laughter.

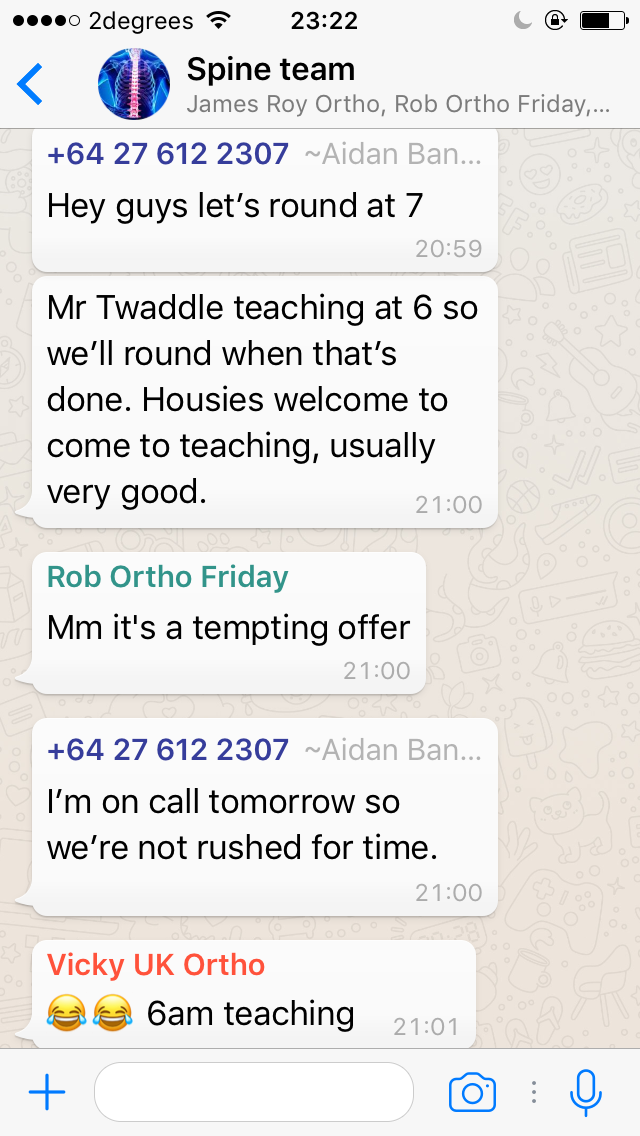

Despite the long hours and tough bosses, the regs were generally pretty chill. Every other day they would lead the morning round on their team’s patients, and they were some of the most fun and efficient rounds I’ve participated in. The purpose of a “round” is to check in on how your patients have been overnight or (in surgical specialties) how well they are recovering post-operatively, and decide upon any changes in their management (ie looking out for any early signs of infection, making any adjustments to medications, determining whether they need more input from physiotherapists, or social workers, etc). You will usually see all of the patients under your team, which admittedly can be long and tedious, and I have friends who have chosen a specialty in large part to avoid this. (Ahem, Clare! <3 )

Personally (controversially), I find they can be one of the best parts of hospital medicine. I love teamwork, and I love that fast-fire semi-intuitive communication that develops once you’ve been working in a team for a little while, and is so crucial to the flow of the round. I like the little windows of patient interaction that you get, and the little nuggets of teaching. I like being on my feet, on the go. I like feeling as though I have a grip upon all of my patients, that I know what their current issues are, and what we’re doing to address them. There is a lot of satisfaction to be had from an efficiently-run round: often your whole day will hang upon how well you set things in action during those first couple of hours at work – both in terms of jobs (booking theatres, getting scans done, sending off bloods) and in terms of patient contentment. Granted not a whole lot of medicine took place on these Ortho rounds, but there was a lot of team bonding and banter, plenty of Ortho-specific things to see and learn, and they invariably ended with breakfast or coffee. They also offered an insight into colleagues that wasn’t necessarily evident elsewhere. Some of the most intimidating figures could turn positively tender with favourite patients. It was amazing to see the transformation as they would bend over a patient’s wound asking kindly, “now my dear, do you mind if I have a squiz?”

After breakfast, regs would disappear off to theatre, clinics, or the Emergency Department, leaving us house officers to work through the list of jobs generated on the round. During this time they would be contactable within their team Whatsapp group, which would usually consist of a steady stream of patient updates, inappropriate banter, and photos of wounds that would make even relatively non-squeamish people retch.

I feel like I learnt a lot from the regs during this rotation. There were many occasions where I was impressed by their handling of difficult patients and bosses. They were all happy for house officers to tag along in ED and get involved in setting casts, reducing fractures, and so on. They would all try to teach you as much as they could, especially if you made an effort to ask. The role and responsibilities of a registrar are not exactly the same as they would be in the UK, but there is still a massive jump between house officer and reg. It was good to see it done well. I spoke to everyone I worked with about how they had approached that transition, what they had found difficult, what tips they would give to me. I’ve reached that point where I feel comfortable enough in the NZ system now to be ready for a new challenge, and applying for reg jobs seems the obvious next step. I’ll keep you posted on that, but keep your fingers crossed for me?

Having said all of that, not everything was perfect. Certain individuals were better leaders than others, certain teams ran more smoothly and happily than others. As a rotator I was able to remain more or less aloof from team politics and discontent, much to my relief (- I hate confrontation). Not everyone was happy, and I learnt as much from situations handled well as I did from ones handled poorly. I saw fear breed a reluctance to accept accountability, stress give way to paranoia, and criticism and reproach doled out in such great doses as to cause genuine misery. I’m sure I will make many such mistakes myself, but I hope I don’t forget these observations, and I hope they help me to handle similar situations with greater insight when I’m faced with them.

A confession. I went into this job with, for want of a better word, a certain degree of attitude about surgeons. There is often a lot of frustration when it comes to interactions between medical and surgical specialties. Medics, as a rule, tend to look down upon what they perceive to be poorly managed situations that occur regularly on surgical wards: patients who didn’t get reviewed as early as might have been desirable, patients started on antibiotics too weak or too broad, etc. The criticism often thrown in the direction of the surgeons is that “they went to med school too, they should be capable of dealing with this”. In theory that makes sense, but after working this job I can see how little understanding it reveals of the actual demands and day-to-day working of a surgical firm. In general, the problem is not that surgeons are incapable of managing medical problems, but rather that they simply aren’t physically present to see them arise or evolve. They work incredibly long hours, longer hours than medics, but only a fraction of those are spent on the ward – and that is not their job, it is not where they are being paid to be. Moreover, given the volume of additional surgical information that they need to retain in order to practise their own job to the highest standard possible, even at the level of a junior registrar, it is of little surprise that they perhaps don’t recall the spectrum of antibiotics used infrequently, or aren’t always up to date on the latest hospital protocols. In Auckland there was a good safety net system in place, whereby patients over the age of 65 would all be reviewed by an Orthogeriatrician, who would manage their medical issues during their stay. This system didn’t exist in the NHS hospitals I worked in, and patients received much poorer care as a result, although not through any fault of the surgeons. In those hospitals it would be the poor first and second year doctors trying their best to keep everything together, limited by their relative inexperience, and often filled with anxiety and dread, while the med reg would swoop in to pick up the pieces when shit hit the fan. This was a good example for me of how things can be done better. It was also a reality check. I have definitely shown uncalled-for condescension in the past, I will think twice before doing so again.

Yes that is a massive corrugated iron dog, and a corrugated iron Jesus.

One of my favourite parts of Ortho was the time I spent in the operating theatres. Not that I got to do all that much, but I took so much interest and pleasure in being able to watch operations up close: from the initial ultrasound-guided nerve block, to the first cuts, the careful identification of important structures, the selection of most appropriate metal plates and screws, the x-rays that reveal whether you got it right or messed it up. On my first visit to theatres in Auckland I was fortunate to end up with one of the most humble surgeons I have ever met, also one of the best teachers. He encouraged me to come back as often as I could, and although I actually didn’t get to scrub in with him again until the very end of the run, his encouragement spurred me to put myself out there and make the most of every possible opportunity to watch and learn. It never ceases to amaze me just how much absolute wonder we are exposed to as doctors: such extremes of human emotion, such important life events, such incredibly high levels of skill and lore and craft. I can never get enough of it. There is genuinely no other profession I would rather be a part of.

An update for those of you who have been following my anguish over the past few months re: career decisions and training. I attended a Careers Evening at the hospital the other week and was surprised to realise just how much I’ve learnt about what is and is not important to me in the past six months that I’ve spent working in New Zealand. I do really appreciate the blunt directness of the surgical mindset, and share some of the typically surgical frustration at how slow-paced certain medical wards can seem. I remember one occasion when I went up to visit an Ortho outlier on a medical ward with one of the regs. We passed a group of medics huddled around a computer on wheels deep in debate, and my reg turned to me in genuine perplexment: “medics spend an awful lot of time with COWs, eh? What do they do with them?!”. But as much as I loved Ortho, and as much as I love mastering skills and would therefore enjoy operating, I like too many other things to devote my life to surgery, so that side of things is definitely (if regrettably) out of the picture for me. I’m erring more towards Adult Hospital Medicine now, rather than Paediatrics, for a multitude of reasons that I won’t go into just yet but that I feel I am coming to understand better and (therefore) becoming increasingly happy and at peace with.

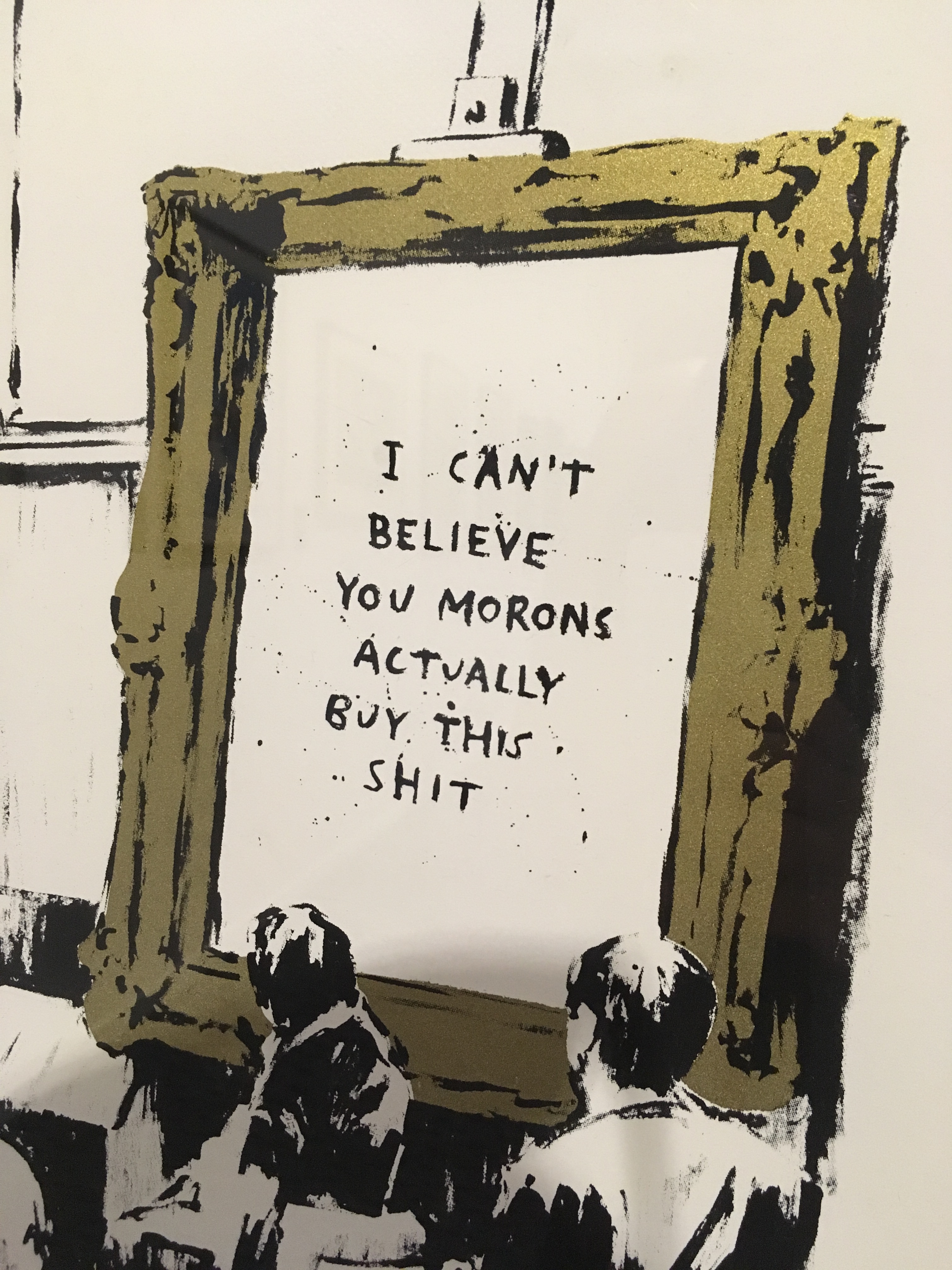

Ahhh, I think it’s probably about time to wrap this up! There’s always so much more I want to write about! The books I’m reading, bach weekends away with kayaking and abseiling and and glow-worm caves, night markets, art exhibitions and theatre performances, existential angst, exotic finds in asian supermarkets, leaving drinks for friends (Bryan! Alex!), mundane evenings at home, and so on and so forth. But there never seems to be enough time to write, and I’m horrifically non-concise (this entry alone is around 5000 words guys I’m so sorry!!!!)… these posts would run to the length of a short novel if I didn’t draw the line somewhere. So in lieu of the above please see the photos running throughout this post, draw upon your imagination to fill in the blanks, and I’ll end on a list of prompts and scattered thoughts instead, because I never was any good at planning essays, and never will be.

Things I’m loving recently: how goddamn lucky I have been with every single one of my rotations, dinners with friends, such kind comments from colleagues, deep blue skies and sunny afternoons, rainbows and pink clouds on the way to work, hedgerows erupting in flower after I thought Autumn had set in, friends in town for the day, NZ wines, twelve hours of sleep after ten days of work, movies and trashy TV with flatmates, taro milk tea, Tui birdsong and cicada choruses, stolen evenings in crazy schedules.

And some things I’m missing especially much recently: caffeine-free tea, mama and papa, sibling hugs and bed nests and gossip girl re-runs and grand designs, messy family dinners and shared Guardian Quick Crosswords and rambling walks, all of y’all friends and family I love so much <3

Some final thoughts.

Isn’t it strange how you can go do big scary things, like leaving everyone you love behind and moving to the other side of the world, and yet the little things still scare you just as much: meeting new people, first days in a new job, telling someone how you feel about them. I think I thought perhaps that doing big scary things would make me better at handling these more mundane situations, but I don’t think I’m any less scared at all.

Another one. I am so happy out here, and I know I’ve written about it a lot on here, but most of the time in real life I try to keep it at least somewhat in check, and I get worried that I’m driving people insane by pointing out all of the little things that I find so full of wonder and beauty. But at the same time I remember the days I longed for the things I have now, and I am so very grateful for everything, and I don’t want to forget that.

See the baby fern and the hearts in the clover though!

Thank you so much to everybody who reads these rambles. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate it whenever anyone tells me they enjoyed a post, writes to me with a similar experience they’ve had, asks me when my next blog is due, and so on. It’s been one of the most wonderful and unexpected side effects, as it were, and I am incredibly grateful for all of the conversations it has started and good things it has brought my way.

Morning sky from my deck as I get ready for work. Spot the moon!

Loving you more than ever – Zx